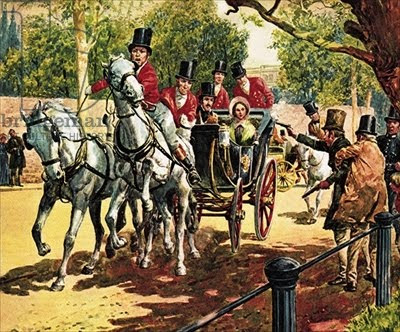

the Queen was worried by a number of more or less crazed individuals who would have liked to share her greatness. This mania to marry the young Sovereign took various forms. One man used to drive his phaeton in front of, or behind, the royal carriage whenever an opportunity offered, and make a nuisance of himself by waving or kissing his hand to Her Majesty. Another lunatic went through a sort of dumb show of the same kind in the Chapel Royal, while a commercial traveller, named Willets, galloped alongside the Queen’s carriage, and almost over her attendants, in his mad desire to reveal the state of what he might have termed his heart. These men were dealt with in ways best suited for the disposal of harmless monomaniacs.

Two examples of this behaviour should suffice. Captain John Goode had, on the 24th of May, 1837, been taken into custody for "creating a disturbance and forcibly entering within the enclosure of Kensington Palace" on the Queen's birthday. Less than six months later, on 4 November, as the Queen was returning from Brighton, Goode came up to her carriage and "made use of most insulting language towards Her Majesty and the Duchess of Kent. Goode was a gentleman with a large property in Devonshire and was apparently quite mad. When he was examined before the Privy Council, he told them "that, if he could but get hold of the Queen, he would tear her in pieces." After a short period of imprisonment, he was sent to a lunatic asylum.

The most interesting case of a lunatic pestering the Queen was that of “The Boy Jones” as he was commonly known. On Thursday, 25 March 1841, Thomas Raikes wrote in his Journal,

A little scamp of an apothecary’s errand-boy, named Jones, has the unaccountable mania of sneaking privately into Buckingham Palace, where he is found secreted at night under a sofa, or some other hiding-place. No one can divine his object, but twice he has been detected and conveyed to the Police-office, and put into confinement for a time. The other day he was detected in a third attempt, with apparently as little object.

A highly fictionalized version of the story was made into the 1950 film The Mudlark with Irene Dunne, Alec Guiness and Andrew Ray.

From 1849, the attacks against the Queen seem to have become more serious. In that year William Hamilton fired a powder-filled pistol at Victoria's carriage as it drove down Constitution Hill, London. She appears, from her correspondence, not to have been overly alarmed, writing to her uncle Leopold to assure him that it was nothing more than "a wanton and wicked wish merely to frighten," although she did view it as "very wrong." Once again, much to Victoria’s delight, the people rallied around her. "The indignation, loyalty, and affection this act has called forth is," she wrote, "very gratifying and touching."

On the evening of 27 June 1850, in what The Illustrated London News referred to as an "atrocious" and "most diabolical act," there was a more serious assault on the Queen. In what seemed to be a senseless attack, a tall, respectable looking, balding man with a mustache, ex army officer, Robert Pate, struck Victoria on the cheek and in the forehead with the brass ferule of a partridge stick as she was leaving Cambridge house with three of her children. She had called to inquire about the Duke, her uncle’s failing health.

|

| Robert Pate Attacking the Queen |

In her letters she described the incident as "very disgraceful and very inconceivable" and it left her bruised, if not bloodied. Even so, later in the evening she attended the Covent Garden Italian Opera to see Meyerbeer’s, Le prophète, where she was given a rapturous welcome. But the attacks were beginning to take a toll on the Queen who admitted to being nervous when she was out in her carriage confessing in a letter to the King of the Belgians, "I start at any person coming near the carriage."

Pate was tried in the Central Criminal Court, and despite a catalogue of “eccentricities” was found sane and guilty and was sentenced to seven years transportation which he served in Van Diemen’s Land.

On the last day of February 1872, the Queen was being driven in an open landau when 17-year-old Arthur O'Connor (great-nephew of Irish MP Feargus O'Connor) appeared at the side of the carriage as it stopped. In her journal, Victoria described the event and was much more open regarding her feelings than in her letters to her uncle in which she described the earlier attempts.

It is difficult for me to describe, as my impression was a great fright, and all was over in a minute. ... suddenly someone appeared at my side, whem I at first imagined was a footman, going to lift off the wrapper. Then I perceived that it was someone unknown, peering above the carriage door, with an uplifted hand and a strange voice. ... Involuntarily, in a terrible fright, I threw myself over Jane C[hurchill]., calling out, ‘Save me,’ and heard a scuffle and voices!

John Brown, who was attending the Queen, grabbed O’Connor and he was arrested and brought before the Court on 2 April at which time he pleaded guilty to the charge of treason. Although an attempt was made to declare him insane, a jury later found "that the prisoner was perfectly sane when he pleaded guilty to the indictment and perfectly sane now." He was sentenced to a years' imprisonment and twenty strokes with a birch rod. The latter was remitted.

Apparently, O’Connor suffered from some degree of mental disorder and this probably accounted for his relatively light sentence. It appeared that his attempt to reach the Queen was to petition her for freedom for a number of Fenian prisoners.

The final attempt on Victoria’s life was, once again, the work of an apparent lunatic. On 2 March 1882, as her carriage left Windsor railway station for the castle, a "wretchedly clad man" fired a pistol at the Queen from a distance of approximately 30 yards. The assailant was Roderick Maclean, a disgruntled poet, apparently offended by what he saw as Victoria's refusal to acknowledge one of his poems. As he was hustled away by police, schoolboys Gordon Chesney Wilson and Leslie Murray Robinson, from Eton College belaboured him over the head and shoulders with their umbrellas. Not all of their exertions were, however, strictly on target. William John M’Closkie, the Landlord of the Star and Garter, told the Board of Magistrates convened at Windsor that in the melee that followed the apprehension of Maclean, "I was hit over the head with an umbrella, the blow being intended for the prisoner."

|

| Maclean on trial for treason |

Despite Mclean’s insistence that his only intention was to frighten the Queen, all of the evidence suggested that there was more to the attempt than that. The finding of bullets apparently from the gun McLean used seemed to remove any question of his having only fired blank cartridges.

The crowned heads of Europe which, by this time were resting increasingly uneasily, sent their congratulations to Victoria on having survived the attack. Churches offered prayers of thanksgiving for her life having been spared even while Maclean was bound over to be tried for high treason at the Berks Assizes on 19 April 1882.

It was clear both before, during and after the trial that Maclean suffered from a significant mental disorder. The Professor of psychology at King’s College and Medical Superintendent at Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum for twenty years, testified that Maclean was "unquestionably of unsound mind." An opinion concurred in by a number of other witnesses.

In the end it took a jury only twenty minutes of acquit Maclean on grounds of insanity, knowing, from The Lord Chief Justice’s charge, that if they were to so acquit him he would be "safely detained during the Queen’s pleasure."

The ultimate word, on this final attempt to assassinate the Queen, must go to William Topaz McGonagall, considered by many to be the worst poet in the history of that genre. To read his poem, "Attempted Assassination of the Queen," click here.